Why are we asking this now?

Because yesterday the Government was forced into a climb down over its refusal to allow all former Gurkha soldiers to settle in the UK after they had left the British Army. It had faced a Commons defeat over the restrictive policy it had introduced in response to a High Court ruling last year that Gurkhas who left the Army before 1997 – when the Gurkhas' base moved from Hong Kong to Kent – had an automatic right of residency in the United Kingdom.

The changes it had announced earlier this week were hedged about with so many conditions that campaigners said only a few hundred veterans would ever qualify. The Government had said that the changes would allow around 4,300 more former Gurkhas to settle here out of the 36,000 who served in the British Army before July 1997. But yesterday the Home Secretary Jacqui Smith pledged to carry out an immediate review of the policy.

Where are the Gurkhas from?

The 3,500 Gurkhas in the British Army all originate from the hill-town region of Gorkha, one of the 75 districts of modern Nepal. But their name comes not from the place but is said to derive from an 8th century Hindu warrior-saint Guru Gorakhnath. Legend has it that it was he who gave the Gurkhas the famous curved bladed knife, the kukri. The Gurkhas are mainly impoverished hill farmers.

How do they come to be in the British Army?

Almost 200 years ago troops in support of the British East India Company invaded Nepal. They suffered heavy casualties at the hands of the Gurkhas and signed a hasty peace deal and offered to pay the Gurkhas to join their army. A soldier of the 87th Foot wrote in his memoirs: "I never saw more steadiness or bravery exhibited in my life. Run they would not, and of death they seemed to have no fear, though their comrades were falling thick around them".

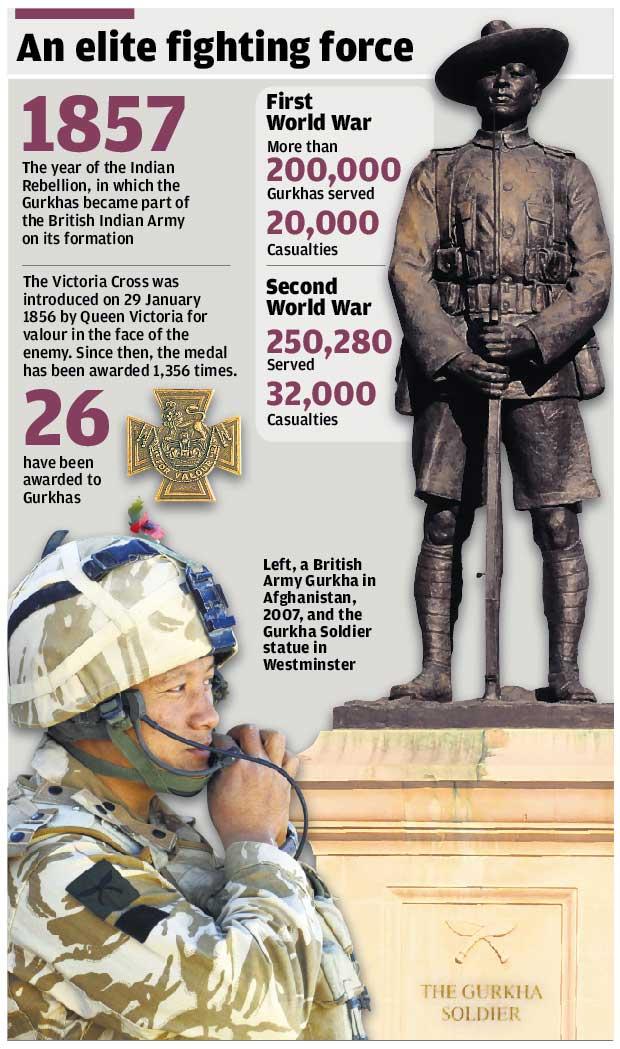

Some 200,000 Gurkhas then fought in the British Army in the First and Second World Wars - in France, Flanders, Mesopotamia, Persia, Egypt, Gallipoli, Palestine, Salonika and in the desert with Lawrence of Arabia and then across Europe and the Far East in World War II. They have since served in Hong Kong, Malaysia, Borneo, Cyprus, the Falklands, Sierra Leone, East Timor, Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Do they serve only in British forces?

No. After the partition of India in 1947, an agreement between Nepal, India and Britain transferred four Gurkha regiments from the British to the Indian army. Its Gorkha Brigade (it changed the spelling) now has 120,000 Gurkhas in forty-six battalions. There are Gurkhas in the Malaysian army and the Singapore Police Force both bodies formed from ex-British Army Gurkhas.

How tough are they?

Around 28,000 Gurkha youths compete for just 200 places in the British Army each year. To qualify they must be able to do 75 bench jumps in one minute and 70 sit-ups in two minutes. Then they participate in the world's most arduous military selection test, the doko - running 5km up a steep track in the foothills of the Himalayas, carrying 25kg of rocks on their back, in less than 55 minutes. No wonder the Gurkhas are famed for their resilience, self-restraint and courage.

Are they really outstandingly brave?

Their motto is "Better to die than be a coward". In the First World War, in which 20,000 of them were casualties, they won almost 2,000 awards for gallantry. At the Battle of Loos in 1915 a Gurkha battalion fought literally to the last man. At Gallipoli they were the first to arrive and the last to leave. Sir Ralph Turner MC who served with them then wrote an epitaph: "Bravest of the brave, most generous of the generous, never had a country more faithful friends than you". If there was a minute's silence for every one of the 23,000 Gurkha casualties from World War II, the nation would have to fall quiet for a full fortnight.

How many Gurkhas have won the Victoria Cross?

There have been twenty-six awards of this highest badge of courage made to members of the Gurkha regiments, half to Gurkhas and half to their British officers – more than to any other regiment.

Some of the acts of bravery were extraordinary, like that of Rifleman Tul Bahadur Pun, now 87, who won the VC fighting the Japanese in the jungles of Burma. Only three of his section survived the onslaught from the enemy. When all his comrades were dead or wounded he snatched up a Bren gun and made a solitary charge across 30 yards of open ground to take a Japanese machine gun which he then used to give covering fire that save a large number of Britsih lives, including that of Major James Lumley, whose actress daughter Joanna is now one of the staunchest campaigners for the Gurkha cause.

What happens after they leave the Army?

Rifleman Pun returned to a tiny Nepalese hill village and raised six children. He lived on an army pension that was a fraction of those of British servicemen, in a small cottage without running water or electricity until his health began to fail. As heart problems, diabetes and asthma assailed him, and he was unable to obtain the drugs to treat them, he applied for permanent residency in Britain – only to be told that, despite being invited to the Queen's coronation in 1953, he had "failed to demonstrate strong ties with the UK".

A more recent veteran is Lance Corporal Gyanendra Rei, 52, who fought in the Falklands. He had his back ripped open by shrapnel, and was left in constant pain, but his application for a visa to enter the UK for treatment on the NHS was refused.

In 2005, after the Gurhkas used the Human Rights Act to appeal against their inequitable treatment compared with regular British army soldiers, the government agreed to increase the Gurkha pension for retirement after 1997 from £95 to at least £450 a month. But there remain 10,500 Gurkhas and 5,000 widows who receive no pension and live in near poverty; they are mostly veterans of the Second World War and are more than 80 years of age. They rely on £6 a month form a Gurkha welfare charity.

Many ex-Gurkhas and their families live in Hong Kong, scraping a living in private security. The United States Navy also employs some Gurkhas as sentries at its Bahrain naval base.

Why won't the Government allow them to live in the UK?

Nepal is not a member of the Commonwealth. Gurkhas have never been subjects of the British Crown. The government says that letting all 36,000 ex-Gurkhas into the UK would lead to "massive pressure" on the immigration service. Gordon Brown has claimed that the country cannot afford to look after them all. But hardly anyone else in the country seems to agree with him.

Should the government allow all ex Gurkha soldiers to settle in the UK?

Yes...

* The country owes a duty of care to men who have served it with the particular dedication typical of Gurkhas.

* The amounts on money involved a trifling compared with what the government has produced for other causes recently.

* Conditions back in the Gurkha hill villages of Nepal as particularly tough for those suffering from injuries incurred in the Army.

No...

* Nepal is not a member of the Commonwealth and Gurkhas are not British subjects.

* Letting in all 36,000 ex-Gurkhas into the UK would lead to "massive pressure" on the immigration and social services.

* The country has to balance its duty to the Gurkhas with its reduced abilities to finance such deals.